You know how much we love our rugs, right? With today's post you will understand that Berber rugs have been loved by eclectic and eccentric personalities, by artists, painters and architects of world renown. In short, we are a little biased, but as you will discover by reading, these artifacts represent a form of art and culture that has always been appreciated, and with a timeless style.

Let's start by saying something "trivial", if you like: in the Western world, rugs have always played a key role in interior design, but they have become true works of art under the influence of famous designers and internationally renowned architects. Since the dawn of modern architecture, the founding fathers of interior design as we know it today have chosen iconic rugs to enrich their projects and their homes, transforming them into distinctive elements of style and elegance.

From Bauhaus textile masterpieces to more contemporary creations, rugs loved by famous designers have redefined the concept of interior decoration.

This journey through the textures and colors of the most famous creations will lead us to discover how these textile works have marked the history of design, leaving an indelible mark to the present day. And we are very pleased to remember that it is precisely our Moroccan rugs that have played a leading role in this splendid story.

Follow us, in short, in another of our very long posts. To quickly orient you, know that we will talk about:

- Orientalism: When Morocco Enchanted Modern Art

- Eugène Delacroix's Journey to Morocco

- Mariano Fortuny y Marsal: From War Painter to Realist Orientalist

- Henri Matisse: Tangier Panoramas and Domestic Views

- Jacques Majorelle: art, life in Marrakech, the creation of the famous gardens

- Paul Klee and Vassily Kandinsky: Africa of Dreams, Memories, Abstract Landscapes

- Moroccan Rugs and Design: 20th Century Architecture

- Famous rugs: When Alvar Aalto Introduced Beni Ourain to the World

- Marcel Breuer and the African Chair

- Charles and Ray Eames, a house to live and love

- Frank Lloyd Wright and the rugs of the most famous villa in the world: Fallingwater

- Focus | Women and Bauhaus, when weaving was the only form of design allowed

- Yves Saint Laurent: colonial atmospheres and Moorish style

| As always, we remind you that the use of the term Berber represents for us an exception to the rule because as we have explained here we prefer to use Amazigh, or - more generally - Moroccan. In this regard, for those who want to learn more about all types of rugs there is a very detailed post on what Moroccan rugs are called . |

Orientalism: When Morocco Enchanted Modern Art

Western art of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries has often looked to the East with dreamy eyes, in search of light, colour, new harmonies.

For some artists, however, the trip to North Africa was not just an exotic suggestion, but a true interior and stylistic revolution. From Delacroix's detailed diaries to Klee's rugs of light, from Majorelle's bright blues to Fortuny's hypnotic fabrics, to Kandinsky's interior landscapes and Matisse's chromatic rhythms: Morocco and its neighboring countries have left a profound mark on modern art.

A journey through the eyes of these artists is also a journey into color, matter and the very essence of painting.

We are sure you will be fascinated too.

Eugène Delacroix's Journey to Morocco

In 1832, the French painter Eugène Delacroix visited Morocco as part of a diplomatic mission , a trip that left a profound mark on his art, especially in his color palette and meticulous attention to decorative detail. Scenes of everyday life, traditional clothing, and intricately patterned rugs became recurring elements in his works, helping to spread the Moroccan aesthetic in Europe .

Eugène Delacroix "Jewish Wedding in Morocco". Source: Wikimedia Commons , public domain image.

I go for walks which give me infinite pleasure, and I have moments of delicious laziness in a garden at the gates of the city, under the abundance of orange trees in bloom and covered with fruit.

His Moroccan travel diaries made available by Google Arts and Culture are full of stories, images, and suggestions.

Delacroix was not looking for the bazaar, he did not yearn at all costs for an artificial “picturesque”: he painted the authenticity, the intimate and domestic spaces to which he had the privilege of access thanks to his friendships with leading figures of the Jewish community of Tangier.

In his notebooks he meticulously noted the colours and fabrics - white, red, velvet green, light green - and drew Arab houses by studying the local architecture in depth, of which he represented typical elements such as tiles, doors, windows and niches.

From Morocco and Algiers he brought back studies that were then reused in some of his paintings, the most famous of which are "The Jewish Wedding in Morocco" and "Women of Algiers".

In short, an experience so powerful and revolutionary that it influenced all of his subsequent artistic expression.

Eugène Delacroix "A Moroccan Couple on Their Terrace". Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org , public domain image (Met's Open Access policy).

Mariano Fortuny y Marsal, from war painter to realist orientalist

There are journeys that, even if born under an unlucky star, change your life. For Mariano Fortuny y Marsal, Morocco was just that.

In 1860 Fortuny was sent to Africa to document the Spanish-Moroccan war. But while many artists would have reconstructed only glorious battles and soldiers on canvas, he went much further. He was won over by the colors and the light, the bustling markets, the streets of Tetouan, the splendid fabrics and the intricate architecture of the Moroccan cities .

His paintings will not tell of the war, but of the warmth of the sun on the white walls, the liveliness of the decorated caftans, the mystery of exotic interiors.

From that moment on, the fascination of what was then considered "the Orient" never abandoned him. And although his life was short, his trip to Morocco remained imprinted in his paintings, making him one of the most extraordinary interpreters of a dreamed, but deeply lived Orient.

Mariano Fortuny "Maroon Woman". Source: Wikimedia Commons , public domain image.

Mariano Fortuny "The Cafe of the Swallows". Source: Wikimedia Commons , public domain image.

Henri Matisse: Tangier Panoramas and Domestic Views

Henri Matisse arrived in Tangier in 1912, at a time of great uncertainty. He was just over forty, at the height of his career, but the death of his father had left him in a deep artistic crisis. He felt the need to break away from Fauvism and seek a new path, and Morocco offered him exactly what he was looking for: light, color, rhythm. He spent two winters in a row in Tangier, fascinated by the contrasts of this city suspended between land and sea, between the din of the souks and the silence of the Moroccan interiors.

Here he fell in love with Islamic art, with arabesques, with saturated colors that seemed to pulsate with a life of their own. The azure blue, the blue, the turquoise conquered him, transforming his painting. The forms became simpler, the light became the absolute protagonist. The Moroccan interiors, with their rugs, the geometric tiles and the play of shadows and reflections , taught him a new way of looking at space. After his stay in Morocco, green and blue became his guiding colors, those that would mark his painting in the years to come.

He painted not only the landscapes of Tangier, but also the intimate atmospheres of Moroccan rooms with their protagonists, where the light filtered through light curtains and every object seemed to be part of a perfect composition. What he found in Morocco was not only inspiration, but a lesson in essentiality: the idea that beauty could be born from synthesis, from a few elements put in harmony. A lesson that he would carry with him forever.

Look at these shades of blue and green!

Henri Matisse "Zorah on the Terrace". Source: Wikimedia Commons , public domain image.

Henri Matisse "The Window at Tangier". Source: Wikimedia Commons , public domain image.

If you are also fascinated by Matisse's love for Morocco, you absolutely must watch this video .

Jacques Majorelle: art, life in Marrakech, the creation of the famous gardens

If you have been to Marrakech at least once in your life – and if you haven’t, we highly recommend it! – you will have surely visited the wonderful Majorelle Gardens .

Now home to the Musée Pierre Bergé des Arts Berbères and the Musée Yves Saint Laurent , their history began in 1931, when the painter Jacques Majorelle created them as a space of inspiration and refuge. In 1980, Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé purchased them, saving them from privatization and transformation into a hotel, and opened them to the public. The splendid house in the center of the garden, initially the artist's studio and home, was designed by the Parisian architect Paul Sinoir and blends, in astonishing compositional harmony, cubism and Moorish style.

"Jacque Majorelle's Study in the Jardin Majorelle Botanical Gardens (Marrakech)" by FriedrichFrisch, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Source: Wikimedia Commons .

And then there is him, the very famous “Majorelle blue” . Even before Klein, Jacques Majorelle was one of the very few artists to give his name to a color: an intense, vibrant blue, between cobalt and ultramarine.

If you fell in love with it, here is the hex code #6050dc to reproduce it on the walls of your home!

This rich vibrant shade, similar to cobalt and ultramarine, is inspired by the zellige glazed earthenware (from the Arabic ﺯﻟﻴﺞ, zullayj, ceramic, small polished stone) and the lapis lazuli blue used in the wood decoration called zouaq. You will find it everywhere in the Majorelle Gardens, enveloping everything in a magical atmosphere.

"Marrakech Majorelle Garden 2011" by Bjørn Christian Tørrissen, CC BY-SA 3.0 license. Source: Wikimedia Commons .

Gorgeous!

Jacques Majorelle was not only an incredible colorist, but also an extraordinary painter. Son of an artist – his father was Louis Majorelle, a famous Liberty and Art Nouveau designer – he settled in Marrakech in 1919 and was enchanted by its colors and architecture. He painted souks, casbahs, ksours, immortalizing Morocco with a sharp and almost photographic line, and even designed advertising posters to attract European tourists. His modern gaze and deep love for Morocco still lives today in his works… and, of course, in the blue that bears his name.

"The Tinghir Kasbah" by Narbonne, CC BY-SA 3.0 license. Source: Wikimedia Commons .

Here you can find an interesting tribute to the artist (a short brochure in English that collects some of his works and his story).

Paul Klee and Vassily Kandinsky: Africa of Dreams, Memories, Abstract Landscapes

Paul Klee visited North Africa twice in his life , and those trips left an indelible mark on him. Although he never set foot in Morocco, his experiences in Tunisia in 1914 and Egypt in 1928 transformed the way he painted. He was fascinated by the light, colors and architecture of those places, and simplified forms, vibrant surfaces and warm tones, inspired by the North African landscapes, began to appear in his paintings. In Tunis, together with the artists August Macke and Louis Moilliet, he painted works in which the outlines of houses, mosques and alleys dissolve into patches of pure color. It was there that he wrote the famous phrase: "Color and I are one," the sign of a true artistic revelation.

"Hammamet with Its Mosque" by Paul Klee, 1914. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Released into the public domain through the Open Access program. Source: Wikimedia Commons .

The trip to Egypt in the winter of 1928-29 pushed him even further. Here his works began to resemble rugs of lines and colors , with overlapping stripes that build depth, like a horizon vibrating in the heat of the desert. Although at first glance they seem abstract, these compositions recall the movement of the wind on the sand or the glow of a fire burning in the golden evening air. A perfect synthesis of form, color and atmosphere.

"Fire in the Evening" by Paul Klee, 1929. Faithful photographic reproduction of a two-dimensional artwork in the public domain. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York. Source: Wikimedia Commons .

This is the meaning of the happy hour: I and the color are one.

Vassily Kandinsky also discovered North Africa, but a few years earlier, between 1904 and 1905, when he was still looking for his way among the impressionist influences.

He visited Tunisia and was struck by the strong contrasts, the geometric decorations, the colours of the majolica tiles and mosques.

He was not yet the abstract artist we all know: his style was still evolving, but already in his paintings of that period we can glimpse something new, an interest in the simplification of form that would lead him, a few years later, towards Expressionism and the definitive turning point of abstraction.

According to scholars, it was the encounter with the perfect geometries of Islamic art that pushed him to abandon naturalism and explore a visual language made of signs, colours and symbols .

"Arab City" by Vassily Kandinsky, 1905. Courtesy of the Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. Faithful photographic reproduction of a two-dimensional artwork in the public domain. Source: Wikimedia Commons .

"Arabs (Cemetery)" by Vassily Kandinsky, 1909. Courtesy of the Kunsthalle Hamburg. Faithful photographic reproduction of a two-dimensional artwork in the public domain. Source: Wikimedia Commons .

For both, North Africa was not just a travel destination, but a place of the soul, an experience that transformed their way of seeing and painting . Real landscapes gave way to interior ones, and color became the true protagonist of their works.

Moroccan Rugs and Design: 20th Century Architecture

In short, at the beginning of the twentieth century, Berber rugs and Moroccan culture fascinated and inspired many European artists, profoundly influencing abstract art and cubism.

We have already talked about Paul Klee and Vassily Kandinsky, but we have not yet mentioned that both were also teachers at the Bauhaus, the famous school of art, design and architecture active in Germany between 1919 and 1933. The Bauhaus was a true laboratory of innovation, a meeting point for artists, architects and designers from all over the world, where ideas and experiments mixed freely. The theories developed in those years would revolutionize not only art and architecture, but also industrial design, typography and even craftsmanship, leaving an indelible mark on the visual and functional design of the 20th century.

The founder of the school, Walter Gropius, was a key figure in the Modern Movement, along with Le Corbusier and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. The legacy of the Bauhaus continues to influence architects, designers and artists around the world today. And Le Corbusier, a great lover of Berber rugs, collected them and displayed them in his home in Paris. He taught his students at the École des Beaux-Arts et d'Architecture a key principle:

"Do as the Berbers do, combine geometry with the wildest imagination."

But it was Alvar Aalto who made one of the most iconic rugs famous. He, like many of his contemporaries, was influenced by the Bauhaus, especially by László Moholy-Nagy. Along with Le Corbusier, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Walter Gropius and Frank Lloyd Wright, he is considered one of the fathers of the Modern Movement.

Here, we were already getting excited. Now let's talk about it in more depth:

Famous rugs: When Alvar Aalto Introduced Beni Ourain to the World

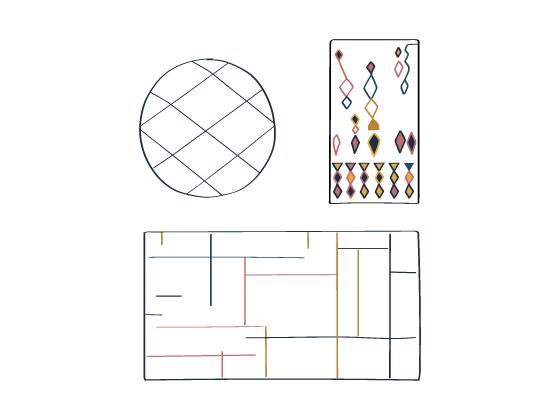

Probably the most famous Moroccan rugs of all are the Beni Ourain : you may not have heard the name but it is almost impossible that you have not seen at least one in some interior photos, especially if in Scandinavian style: this type of black and white diamond-shaped rug with long pile is also popular in the homes of influencers and has been photographed practically everywhere.

But in the early 20th century, Alvar Aalto was among the first modernist architects to incorporate Beni Ourain rugs into his interiors .

These luxurious wool rugs , with their thick weaves, added warmth and comfort, toning down the minimalist look of the modernist spaces typical of the period. The rough weaving technique, abstract geometric designs and neutral colours of the rugs perfectly matched the philosophy of modernism, which aimed for pure and essential art.

One of the most iconic Beni Ourain , with its black and white diamond design, stands out in the images depicting Aalto's personal studio, designed in 1955.

"Studio Aalto 2023" by Jonathan Platteau licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Source: Wikimedia Commons

(If you're wondering what so many Ikea stools - designed in 1980 - are doing in Aalto's studio, keep reading!)

But his passion for Berber rugs began a few years earlier.

Hugo Alvar Henrik Aalto, a Finnish architect and designer, was one of the most influential figures in shaping the aesthetics of Nordic and Scandinavian design. His approach was based on the principle of Gesamtkunstwerk, a total work of art that involved the complete design of an environment: from the building itself to the furniture, lighting and objects.

In 1935, together with his wife Aino, Maire Gullichsen and Nils-Gustav Hahl, he founded the famous Artek company, a design workshop that dealt with furniture, textiles and glass objects. Aalto was also one of the first to use bent plywood, with his famous stacking stool, armchair and bentwood trolley becoming globally recognized design icons.

So famous that they were then cleverly imitated. Yes, those in the photo are the Artek stools, which Ikea then - to put it mildly - reinterpreted thirty years later. And the absurd thing is that the latter are more familiar to the public than the originals.

The story of Berber rugs for Aalto began in the summer of 1935, during a trip with Aino through Europe to study the latest trends in architecture and design. In Zurich, Aino made contact with the design shop Wohnbedarf, which became a key source of inspiration for Artek, thanks to its display of Berber rugs. Wohnbedarf's North African Folk Art Exhibition featured Amazigh rugs, produced by Amazigh people using traditional weaving techniques: perfect for the modernist design aesthetic and evolving Brutalist architecture.

"The Aalto House, Helsinki" by Ninara licensed CC BY 2.0. Source: Flickr

Wohnbedarf and Artek shared a rug supplier in Morocco, and those textiles exhibited in Zurich had a profound effect on Artek’s aesthetics and product choices. Berber rugs were thus used not only in the Aaltos’ private home, but also in projects for private clients such as the Villa Mairea and Villa Skeppet (below).

"Villa Mairea" by Andrew Carr licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. The image has not been modified. Source: Flickr

"Interiör från Villa Skeppet" by Göran Schildt. Courtesy of the Swedish Literature Society in Finland. Public domain CC BY 4.0 license. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In 1936, Artek created a “model apartment” in Helsinki, on Minervankatu, where he exhibited furniture and accessories from the catalogue. In each room there was at least one long-haired white wool rug, with the characteristic black diamond or zigzag decorations.

"1936 Minervankatu model apartment exhibition, living room". Photo by Heinrich Iffland. Courtesy of Alvar Aalto Foundation. CC BY 4.0 license. Source: ResearchGate .

In the same year, Aalto and Artek organized an exhibition at the Helsinki store, which featured a significant selection of Amazigh rugs from Morocco.

And, curiously, do you know who designed the Wohnbedarf shop? Marcel Breuer!

Marcel Breuer and the African Chair

Creator of the Wassily armchair and the first cantilevered Cesca chair in tubular steel and rattan, Marcel Breuer had a special relationship with Morocco, a country he visited between 1932 and 1935 , where he was deeply influenced by the local artistic traditions. During his stay, Breuer had the opportunity to come into contact with Moroccan culture, exploring its art, its architecture and, above all, its rugs. The latter, as for other modernist designers and architects, represented a direct link to simplicity, craftsmanship and geometry, which perfectly resonated with the ideas of the Modern Movement and the Bauhaus.

In the context of Morocco, Breuer not only gathered inspiration for his designs, but also began to incorporate elements of that culture into his creations. His exploration of Moroccan rugs, for example, led him to consider the use of fabrics and textures that could evoke a more organic and natural vision, capable of responding to the aesthetic demands of modern design.

Also in relation to the " African Chair " designed in 1921 with Gunta Stölzl*, Breuer showed a growing interest in non-European art forms and cultures, including Africa and North Africa, as a point of reference. In this chair, the use of natural materials such as wood and rattan evoked a connection with traditional non-Western practices, paving the way for a new aesthetic vision that would include other cultural traditions, such as the Moroccan one.

> Let's talk about Gunta Stölzl and the women of Bauhaus in the paragraph: Focus | Women and Bauhaus, when weaving was the only form of design allowed

Furthermore, Breuer was among the most important architects to experiment with the connection between art and architecture, bringing an integrated approach to the design of interiors and architectural spaces, as in the case of the house designed for Walter Gropius, where the tapestry rug replaced the traditional headboard of the bed, an element that symbolized a fusion between functionality and decoration (in this case the rug is not Moroccan but it seems to us an excellent starting point for the original use of rugs!).

"Gropius House Master Bedroom" by SHendry11, CC BY-SA 4.0 license. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The influence of Morocco on Breuer was not only aesthetic, but also philosophical : his search for a synthesis between modernism and tradition, between purist forms and the use of natural materials, was very close to the vision of Moroccan craftsmen, who through the weaving of rugs and other artefacts conveyed a strong connection with nature, geometry and spirituality. This interest in Moroccan culture was an element that enriched Breuer's path , both in design and architecture, giving life to innovative solutions that are still appreciated today for their elegance and modernity.

Charles and Ray Eames, a house to live and love

Aalto's aesthetic had a major impact on the work of industrial designers Charles Eames and Ray Kaiser, who, like their contemporaries, sought to create a dialogue between modernity and tradition, functionality and beauty.

Among the most influential designers of the 20th century, the Eameses revolutionized the approach to design and architecture, integrating innovation with a strong focus on art and functionality. Their creative partnership extended to numerous fields, from the design of iconic furniture such as the famous Eames lounge chair to interior design, photography and even film. During their travels, especially to Marrakesh in the 1950s, the Eameses were inspired by Moroccan culture and, in particular, by Berber rugs , which became a recurring element in their interior designs. The rugs, with their geometric patterns and intense colors, perfectly integrated with the minimalist and functionalist aesthetic typical of their design, creating elegant and welcoming spaces. These rugs not only enriched their creations, but also reflected an interest in simplicity and craftsmanship, themes dear to the Eameses, who believed in the union of beauty and functionality.

One of the most famous examples of how Berber rugs were incorporated into their designs can be seen in the house that Charles and Ray Eames built in Los Angeles - Pacific Palisades, California. In this environment, Berber rugs were mixed with wood and steel furniture, with a perfect balance between natural materials and modernism. The use of rugs gave warmth to minimalist spaces, creating a fascinating contrast with the clean and sharp lines of their chairs and armchairs.

"Eames House" by Edward Stojakovic licensed under CC BY 2.0. The image has not been modified. Source: Flickr

"Eames House Living Room, 1949. Case Study House No. 8. LACMA" by Rob Corder licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0. The image has not been modified. Source: Flickr

The villa fully represents their approach, with its minimalist yet welcoming structure, capable of reflecting a perfect balance between modernism and personal touches. Composed of two rectangular pavilions in glass and steel, on one side the residential area, on the other the studio and the laboratory, it is a perfect mix between minimalism and maximalism, creating an environment that transmits modernity, spontaneity, optimism and an open-mindedness that makes this house unique.

Photographs of the villa often depict the Eameses sitting on the floor in the living room, surrounded by intricate Moroccan rugs with geometric patterns , typical of Beni Ourain rugs . These rugs, with their mix of red, black and orange, represent an element of visual contrast to the other furnishings, yet they integrate perfectly into the environment, enriching the space with their energy and their history. The living room is a true expression of an eclectic aesthetic (which we could also define as a bit boho), where the furnishings and accessories mix naturally and with personality. Each element tells a story, and together they create an atmosphere that cannot be labeled simply: it is not just American, European, Scandinavian, industrial or Japanese style, but a combination of all these influences, which blend into a unique mix.

Charles and Ray Eames poured their entire personality into this villa, taking care of every detail with love. There is no shortage of ready-made pieces, handcrafted objects, gifts from friends, family and colleagues. The house is their style statement, a visual manifesto that pushes the boundaries of conventional design, and that does not hesitate to combine the high and the low, the modern and the traditional, in a harmonious play of contrasts that makes every corner surprising. And, in this context, Moroccan rugs are not simply decorations, but symbols of a search for authenticity, craftsmanship and a perfect fusion between the global and the local.

In 1957, the Eameses began a collaboration with Vitra, a company that continued to produce and distribute their works throughout the world, making their innovative approach to design known to millions of people.

«The details are not the details. They make the product. It will in the end be these details that give the product its life.» Charles & Ray Eames

Frank Lloyd Wright and the rugs of the most famous villa in the world: Fallingwater

Frank Lloyd Wright is universally recognized as one of the greatest architects of the twentieth century. His design philosophy, defined as "organic architecture", aimed to create buildings that would integrate perfectly with their surroundings, blending nature, materials and living spaces in harmonious balance. This vision finds its maximum expression in one of his most famous works: the Fallingwater House, designed in 1935 for Edgar J. Kaufmann, a Pittsburgh entrepreneur.

The house, nestled in the rock above a waterfall, is a masterpiece of lightness and solidity, where every element—from the concrete to the steel beams, to the local stone cladding—contributes to creating an environment in perfect harmony with the landscape. The interiors follow the same logic: integrated furniture, continuous glass walls that dissolve the boundary between inside and outside, and a color palette inspired by the tones of nature.

"Fallingwater, Pennsylvania" by Euelbenul, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Although hundreds of visitors now trample its halls every day, Fallingwater still retains a lived-in charm, as if ready to welcome its original owners at any moment. Although tourists are forbidden to sit, the cushions on Wright’s custom-made sofas are still upholstered in the same richly woven beige fabric as before, and the stone floors of the large living and dining room are decorated with warm-toned Berber rugs .

It should feel like a home, not a state museum.

This choice is not accidental. Wright placed great importance on natural materials and their ability to convey warmth and authenticity. The client's son, Edgar Jr., wanted the house to retain this welcoming atmosphere, as chief curator Lynda Waggoner explains: "It should feel like a home, not a state museum."

And it is precisely this attention to detail, from the Moroccan rugs to the arrangement of the furnishings, that makes the Fallingwater House still today a timeless symbol of balance between design and nature.

"Fallingwater" by Sakul9, CC BY-SA 4.0 license. No changes made. Source: Wikimedia Commons

"Fallingwater - obývací pokoj včetně původního vybavení" by Sakul9, CC BY-SA 4.0 license. No changes made. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Focus | Women and Bauhaus, when weaving was the only form of design allowed

In the 1920s and 1930s, the world was going through profound social and cultural changes, and the condition of women, especially in Western countries, underwent significant transformations. The women's rights movement was gaining ground: people were fighting for the right to vote, for greater access to work, and for new social freedoms. The figure of the "flapper" became an emblem of modernity and rebellion, but in reality the traditional model of women continued to dominate.

The relationship between women and the Bauhaus was particularly controversial, as was often the case with many forms of art and expression . Despite the large number of applications from female students, access was severely limited. And even for those few who were accepted, their options were limited: they could not attend courses in architecture, painting or design, but were directed exclusively to the weaving, ceramics and bookbinding workshops.

"Webereiklasse Webmeister Kurt Wanke, Bauhaus Dessau" by Walter Gropius, circa 1928. Courtesy of the Bauhaus Archive, Berlin. Public domain. Source: Wikimedia Commons

But, as often happens, women’s determination and creativity always find a way to shine through! Those limitations were transformed into opportunities, and the artistic influences of the Bauhaus came to life through textiles and tapestries that, upon closer inspection, reveal surprising affinities with modern Berber rugs.

Gunta Stölzl's work, in particular, immediately recalls the Azilal , the Zindekh and the Boucherouite :

"Tapiseria stworzona przez Guntę Stölzl w latach 1927-1928" by Jennifer Mei. CC BY 2.0 license. Source: Wikimedia Commons

How can we not find Hassira mats in this extraordinary work in cotton, linen, raffia and silver thread by Anni Albers, which we admire in the photo on display at the Tate Modern?

At the Bauhaus, Anni learned from Paul Klee the expressive possibilities of a grid, and in the fabrics of ancient cultures she recognized a powerful visual language. Albers then developed "pictorial textures" elevating the fabric to pure aesthetics. His Holocaust memorial "Six Prayers," commissioned in 1965 by the Jewish Museum in New York, offers the viewer an opportunity for private contemplation and reflection.

"Six prayers" (The Anni Albers show at Tate Modern is astonishing, by Steve Bowbrick), CC BY-SA 2.0 license. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

And what about these ultra contemporary striped designs?

"Anni Albers (1899–1994) Design for a Silk Tapestry 1926" by Art is a word. Source: Flickr , public domain work.

Yves Saint Laurent: colonial atmospheres and Moorish style

Yves Saint Laurent and Morocco: a colorful love story . The French designer, an absolute genius of haute couture, found in Marrakech a second home, a creative refuge and an inexhaustible source of inspiration. His connection with the North African country was so intense that it influenced not only his collections, but also his lifestyle and the way he conceived living spaces. Here's how he himself described it:

"When I discovered Morocco, I realized that the color palette I used was that of zelliges, zouacs, djellabas and caftans. Since then, I owe my bold choices in my work to this country, to its powerful harmonies, its daring combinations, to the ardour of its creativity. This culture has become mine, but I have not only absorbed it: I have annexed it, transformed it, adapted it."

And indeed, anyone who has had the pleasure of walking in his riads and villas in Marrakech will have noticed how his love for Moorish art and French style has merged into a sophisticated and sensual mix. A universe made of horseshoe arches, shaded courtyards, brightly colored mosaics, carved lanterns and Moroccan rugs with soft and enveloping textures.

Speaking of rugs: do you think YSL simply decorated the floors with anonymous industrial fabrics? Absolutely not! The interiors of his residences were a riot of Berber kilims, soft wool Beni Ourain rugs and unique pieces hand-woven by the tribes of the Atlas . All arranged with that mastery that transforms a space into a true aesthetic experience.

But if Saint Laurent and his partner Pierre Bergé had a vision, one man gave concrete form to their dreams: Bill Willis , the American interior designer who revolutionized the way of furnishing the homes of the international jet set. He was entrusted with both the Dar Es Saada villa, purchased in '74 and renamed "the house of happiness and serenity", and Villa Oasis, a Moorish-style residence painted in blue that Saint Laurent and Bergé acquired in 1980 - previously belonging to Majorelle, who created the lush gardens we spoke about above.

Willis reinterpreted the so-called "Moroccan style", updating it with a contemporary touch and fusing it with the elegance of the French style . He is credited with having rediscovered and relaunched decorative details such as sculpted stucco, mosaic fountains and, of course, the magnificent Berber rugs that today we associate with the most refined Moroccan aesthetic.

So, if you ever find yourself walking through the streets of the iconic Jardin Majorelle or the rooms of the Villa Oasis, stop for a moment to admire the rugs under your feet. Behind every knot and every geometric pattern lies a story, made of culture, tradition and a pinch of that creative genius that made Yves Saint Laurent immortal.

Ps: Today Villa Oasis is owned by the Fondation Jardin Majorelle and houses on the ground floor the Museum of Berber and Islamic Arts, a museum that exhibits a collection donated by Bergé, a great scholar and connoisseur of Moroccan art and local cultural heritage.

In conclusion

Bauhaus, rationalism, modernism, brutalism: these currents have marked history and continue to influence architects, interior designers and designers from all over the world. Mid-century design, Scandinavian and Nordic style, industrial style, are inspired and draw heavily from these illustrious predecessors.

And we are happy to say that Moroccan rugs have played a fundamental role in defining the style . But also in softening and humanizing the often very bare and geometric features and materials. And so, the combination of soft rug, wood and concrete have become a must have for the contemporary home.